I strongly believe -- as strongly as I believe anything -- that as physicist Jose Wudka put it: "The scientific method is the best way yet discovered for winnowing the truth from lies and delusion", and therefore that the picture of the world as assembled by the scientific community is the best available to us.

Believers in "fringe" topics tend to describe science and scientists as a closed conspiratorial community of fuddy-duddies concerned with simply rejecting all ideas that aren't part of scientific orthodoxy. This picture is about as far from the truth as possible.

The history of science is the story of the adoption of new ideas, even "crazy, radical" ones --as long as the advocates of these ideas can produce convincing objective evidence for them. It's difficult to think of any idea that is part of "scientific orthodoxy" now that wasn't a crazy radical new idea a few hundred years ago, or even a few years ago.

If you have a new idea that is not currently accepted by science (or, for that matter, an old idea), just prove it, and you will be accepted by science, and very likely win the Nobel Prize. If you find yourself saying "These scientists are just rejecting my 'proofs' in a conspiratorial manner", then the odds are 99% that your proofs are wrong, and that you need to change your ideas, rather than continuing to expect the scientists to change theirs.

I strongly support the "scientific", "skeptical", philosophically naturalistic and materialisticworldview which IMHO is aptly summarized by Isaac Asimov's essay "Knock Plastic":

"... knocking wood (for luck) is only one example of a class of notions, so comforting and so productive of feelings of security, that men (sic) will seize upon them on the slightest provocation or on none at all. ...

I have come up with six very broad Security Beliefs that, I think, blanket the field ..."

- There exist supernatural forces that can be cajoled or forced into protecting mankind.

Here is the essence of superstition. ...

What scientists do is work on the assumption that Security Belief No. 1 is false.- There is no such thing, really, as death.

- There is some purpose to the Universe.

(-- though) ... each of us can so arrange his (sic) own personal life so as to make it meaningful

to himself and to those he influences- (Some) Individuals have special powers that will enable them to get something for nothing.

- You are better than the next fellow.

- If anything goes wrong, it's not one's own fault.

(my parentheses -- ed.)

Don't miss the rest of the article -- Asimov goes into considerably more detail.

Included in Magic; The Final Fantasy Collection by Isaac Asimov

So, the "scientific", philosophically naturalistic, philosophically materialistic converses of these would go something like --

- There are no supernatural forces that can be cajoled or forced into protecting mankind.

- Death is real.

- The Universe has no purpose.

(-- though) ... each of us can so arrange his (sic) own personal life so as to make it meaningful

to himself and to those he influences- No one has any special powers that will enable them to get something for nothing.

- You are no better than the next person.

- You are responsible for your own decisions and actions.

Among the subjects not extensively discussed on this site are the "fringe topics" listed below.

We can loosely divide these into:- The "supernatural" -- things that are "beyond" the natural world. E.g., Life after death, supernatural beings, the power of prayerThere is some overlap between these, and some topics that don't fit neatly into these categories.

- The "fringe natural" or "pseudoscientific" -- aspects of the natural world not recognized by conventional science. E.g., Bigfoot, UFOs as extraterrestrials, alternative medicine therapies

As I've said elsewhere on this site, I don't think there's any good evidence for the supernatural in any form (or to rephrase, I think it makes a lot more sense to interpret reports of "supernatural" phenomena as being, in fact, unusual psychological processes, deluded thinking, and card tricks.)

(However, I am open to modifying my views if additional evidence warrants.)

I feel that the evidence is pretty strong that brief and occasional -- but poorly understood -- "hallucinatory" experiences are not rare in sane ordinary people, and account for many accounts of odd stuff, such as ghosts, space people, big hairy "ogres", etc, etc. (Cf the reasonably well-known and common subjects dreaming, schizophrenia, sleep paralysis).

Note also that there are often strong psychological factors affecting belief in these things."Religion (And I include the "religion-like fringe beliefs" in the same category) is based, I think, primarily and mainly upon fear. It is partly the terror of the unknown and partly, as I have said, the wish to feelthat you have a kind of elder brother who will stand by you in all your troubles and disputes. Fear is the basis of the whole thing -- fear ofthe mysterious, fear of defeat, fear of death. Fear is the parent of cruelty, and therefore it is no wonder if cruelty and religion have gone hand in hand. It is because fear is at the basis of those two things. In this world we can now begin a little to understand things, and a little to master them by help of science, which has forced its way step by step against the Christian religion (and others! The Christians certainly have no monopoly here), against the churches, and against the opposition of all the old precepts. Science can help us to get over this craven fear in which mankind has lived for so many generations.Science can teach us, and I think our own hearts can teach us, no longer to look around for imaginary supports, no longer to invent alliesin the sky, but rather to look to our own efforts here below to make this world a better place to live in, instead of the sort of place that the churches in all these centuries have made it."The section "Fear, the Foundation of Religion"

from "Why I Am Not A Christian"

by Bertrand Russell"I can't accept the idea that the Universe is Godless, random, material, etc." Well, Bucky, the facts of the matter are not influenced by whether you can accept them or not.

People want to believe that there is life after death People want to believe that the health problems of themselves and their loved ones can be cured.People want to believe that there are simple, comprehensible, answers to extremely complex problems. People want to believe that complex issues can be controlled by human beings (or by supernatural "people" who are not human beings), and that we can improve the world by dealing with those individuals. People want to believe that there is meaning in the Universe. Indeed, it's common to hear people say

People say, "I don't like that bad old science because it chips away at belief in the things that comfort me, and without them, I'm afraid." Well, I feel for you. I'm sorry that you are fearful. But I don't think that fear can justify believing or disseminating lies. We have to very, very honestly try to determine what is true and what is not (and what works and what does not), and believe, state, and use the true and effective rather than the false and ineffective.

I should also probably emphasize that in my younger days I was very interested in these topics and read voraciously on them (and continue to take a passing interest in them), so I do have a pretty good idea what I'm talking about. (I.e., Please don't email me about any of this stuff.)

Very big field.

Medicine is perhaps the example par excellence of science's "Question, Test, Accept or Reject" model. When nutty new medical ideas appear, scientists and medical workers rightly say, "Wait a sec, where are you coming from with that?" Then research is done (generally very careful research), and a decision is made whether to implement the new therapy or not.

Alternative medicine enthusiasts often say that alternative therapies are being suppressed by a conspiracy of conventional medicine entities ("Big Pharma"). While I'm generally skeptical of conspiracy theories, I think that large companies sometimes do resort to unethical and even extreme practices to protect their profits. However, we must not lose sight of the fact that there are competing companies not making profits from any given therapy, who would like to develop their own "alternative therapies". If StompCo can prove that crystals cure cancer without the side effects of chemotherapy, they stand to make a tidy little sum from that.

In fact, many therapies which were once "alternative" are now mainstream medicine -- in some cases are now even the basis of medicine.Examples:So, to sum up here --

- Since Roman times people suspected that there was something in swamps which could get into the air and cause malaria ("malaria" means "bad air"). They were perfectly right; the "something" is mosquitos which transmit malaria. In premodern times people eliminated the mosquitos by draining the swamps, in modern times people also use DDT and other pesticides, as well as treating the malaria itself.

- Girolamo Fracastoro, Agostino Bassi, and Robert Koch proposed that many diseases were caused by teeny-tiny "germs" which you couldn't even see with your own eyes. Medical experts said they were nuts.

Ignaz Semmelweis

In 1884 Koch and Friedrich Loeffler finally established what are called Koch's postulates

(In other words, many people that you know were born less than a hundred years after the germ theory of disease was generally accepted.)

- Pasteur, Lister, and Semmelweiss proposed that those little "germs" could be transmitted on people's hands (for example when doctors were performing surgery), and that infection and death could be reduced by people (for example surgeons) washing their hands. Medical experts said they were nuts.

- Pasteur proposed that diseases caused by "germs" could be reduced by "vaccinating" people with a weak form of the disease, so that they'd be resistant to the dangerous form. Medical experts said he was nuts.

Thousands of "alternative therapies" are proposed every year. Doctors and medical companies really honestly do want to develop and use the ones which are really effective, either because they're nice and want to help people, or because they want to make a zillion zillion dollars. On the other hand, we do want to avoid using those therapies which are actually not effective, either because they are harmful in and of themselves, or because we don't want to be focussing on doing a less-effective treatment instead of a better one. As always, the scientific method is the most effective way of determining which is which.

"David Colquhoun published an excellent editorial this week in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) (Secret remedies: 100 years on, by David Colquhoun. BMJ, 15 DEC 2009) in which he looks back at the last 100 years of “secret remedies.” He points out that a century ago the medical establishment and government regulators tried to protect the public from unscientific patent remedies, but those efforts were anemic, and eventually faded away. Now we are in the midst of a resurgence of unscientific remedies, and those who should be protecting the public health are not even mounting a half-hearted defense.

David refers to an 'intrepid, ragged band of bloggers' along with a few journalists who are the only ones pointing out the folly of abandoning the science-based standard of care in medicine."

Considered in historical perspective, has the worst track record of any topic on this page. The ancient Middle eastern societies (Assyrians, Babylonians, Chaldeans) were using it 3,000 years ago, and by Classical Greek times philosophers were already criticizing it as bosh. Again, the history of science is the history of "crazy" ideas being proven right and accepted by the mainstream. If astrology really worked it would be part of mainstream scientific beliefs. The reason that it isn't is because there is no actual evidence that it works.

Atlantis was first described in 360 BC by the the Greek philosopher Plato in a discussion of various forms of government. In an unrelated work Plato also said that human beings were originally created as hermaphrodites with two heads, four arms, and four legs, which the Gods then split into the single-sexed, one headed, two-armed bipedal humans we know today. Additionally, Plato specifically said in his work The Republic that philosophers should lie to people for their own good.

In other words, Plato was not extremely concerned about scientific accuracy, and the modern consensus is that his story of Atlantis was just "a story" that he used to illustrate some of his ideas (incidentally, the effectiveness of this method is illustrated by the fact that thousands of people can tell you about Atlantis who could not tell you a single one of Plato's ideas on government and philosophy.)

Later writers found the story of Atlantis interesting, and some proposed to discover and discuss the real facts about it. They have produced an enormous variety of theories, which don't agree with each other or with the ideas of mainstream science.

The biggest name in Atlantis-as-a-real-place literature is Ignatius Donnelly, who pretty much got the whole ball rolling in 1882 with his book Atlantis: The Antediluvian World. In the early 20th century, Edgar Cayce recounted from trances that the Atlanteans had flying vehicles and "power crystals".

There is a perennial cottage industry of discovering that Atlantis was really in Antarctica, Birmingham, central Africa, Indonesia, Morocco, Sri Lanka, etc, etc, etc. Scandinavia, South America, and the Mediterranean island of Thera seem to have the most enthusiasts, though I'm sure supporters of other locations would disagree.

In 1998 William Ryan and Walter Pitman produced some scientific evidence that the sea level in the Black Sea rose quite suddenly about 5600 BC, flooding a lot of low-lying communities, and speculated that this was the origin of various ancient ideas about "the Great Flood". This theory may very well be true, however, it isn't very close to what Plato said about Atlantis (though stories of floods, localized or "Great", probably influenced his story.)

Every time and place has stories about "lost lands". Most of them seem to be "just stories" rather than historical accounts. (I hope that theorists a thousand years from now won't be arguing that the Land of Oz was really located in Florida or Tibet or the Mediterranean Sea or something.)

The sources for other "lost lands" (Lemuria, Mu, etc.) are even worse than those for Atlantis (primarily various types of mystical visions), as also is any scientific evidence whatsoever for them.

- Lost continents at Cult and Fringe Archaeology

Give me a break. Contrails (so-called "chemtrails) are basically steam (or snow if the air is cold). It's hard to think of any design for a jet engine that wouldn't produce visible contrails. There is, AFAIK, zero good evidence for any chemical or other agents in contrails which aren't a result of ordinary jet engine exhaust, and zero good evidence for any conspiracy.

Based on the evidence that I've seen, it's hard to think of any clearer example of people's desire to believe in things that are mysterious and threatening.

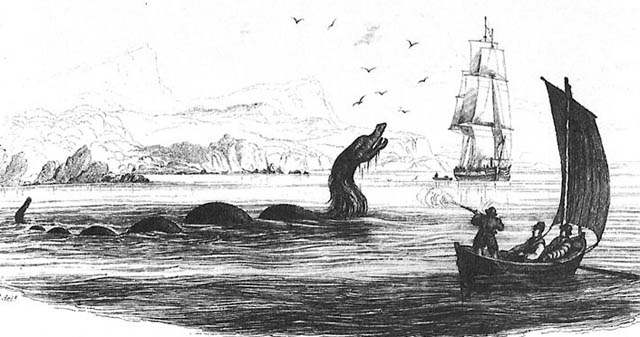

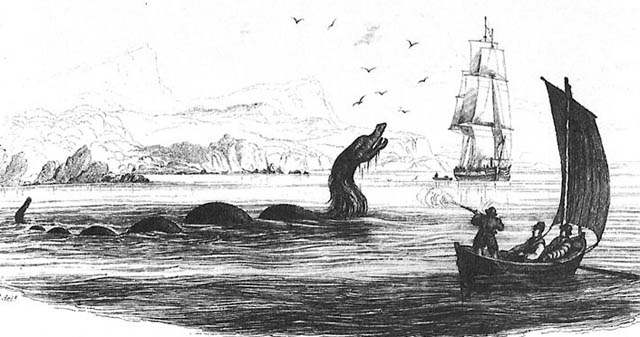

IMHO, Cryptozoology per se is one of the least silly topics on this page -- new species are discovered every year. However, most of them are small tropical frogs, ordinary-looking fish, new kinds of mice, etc, etc.

In contrast, cryptozoology has a very suspicious bias toward large and or spectacular and or carnivorous creatures -- the sort which cannot very well hide under leaves -- and as well for large creatures living in environments devoid of adequate food sources. Yes, lions, giraffes, grizzly bears, and moose exist. And they are well known and are are not mysterious "cryptids".

I'm also very suspicious of the predilection of some cryptozoologists to add new cryptids to the list in line with fossil discoveries.

I've also caught a couple of the faux-documentary-style programs of the "Searching for Mysterious Critters" genre. These seem to have been largely inspired by the recent development of practical self-contained cameras which can be left in the field for days or weeks to hopefully snap photos of cryptids. In every case that I've seen, the photos showed nothing more interesting than crows, foxes, or raccoons, however the local cryptid enthusiasts responded, "This in no way diminishes my belief in the existence of this critter -- I'm just going to continue investigating." Folks, a belief which cannot be affected by evidence is not a valid belief.

- Monster hunting? Well, no. No.

by Darren Naish

Post to the blog Tetrapod Zoology (aka Tet Zoo), 10 OCT 2007

Extispicy, haruspicy, and hepatomancy are various terms for various methods foretelling the future by examining the entrails (guts) of sacrificed animals. For thousands of years this was a popular method of fortunetelling in the ancient Near East and Mediterranean. But for some reason, today you rarely walk past an extispicy parlor or see an ad for a haruspex in the newspaper. It probably is sometimes possible to tell something about environmental conditions from looking at the organs of animals, but in that case, it's not "divination", it's science.

Here's a list of fifty or so traditional divination methods at the Skeptic's Dictionary (skepdic.com). Do these sounds logical to you? If they work, why aren't official scientific, business, and government agencies using them?

"Knowing the future" is very high up on the list of the most interesting topics for human beings. If these things worked, they would be part of mainstream science. (They continue to be popular despite the fact that they are not part of mainstream science precisely because "knowing the future" is so darned interesting to most people.)

No good evidence. IMHO, often the result of brief hallucinations occurring in sane, normal, and sober people. Believed in, now and throughout human history, because people want to believe in life after death.

Again, long track record. I said above that astrology has the longest and worst track record of any subject on this page: magic is a very strong competitor for the honor.

Magic has, I think, a much longer pedigree than astrology; with magic probably being practiced throughout most of the history of Homo sapiens (on the order of 200,000 years), and quite possibly during much of the history of genus Homo itself (2.5 million years or so), while astrology (I'm guessing) didn't become prominent until the rise of agriculture circa 10,000 BCE.

However, I'm giving the palm to astrology since IMHO, doing things which are called "magic" sometimes gets results, while astrology is only right by coincidence.

Or to rephrase this another way, by illustrating it with the pragmatic test --

If I were travelling among some neolithic people, far from "modern civilization" (Western or other "advanced" technology and medicine) and needed some medical treatment, I would accept treatment by an experienced and reputable shaman or healer, and would not be surprised if it showed effectiveness above chance. I would not, under any conceivable circumstances, seek information from an astrologer, and I would never expect astrology to show accuracy above chance.

A wide variety of modalities have been included in "magic": herbalism, physiology, ethology, meteorology, prestidigitation, etc, etc, and obviously enough some of these are perfectly objectively effective -- it's not difficult to make a stone appear, cure a stomach ache with herbs, or predict where the reindeer are going to be. If we strip these out, we are left with the core concept of "real magic": "The art that purports to control or forecast natural events, effects, or forces by invoking the supernatural. 2. a. The practice of using charms, spells, or rituals to attempt to produce supernatural effects or control events in nature. b. The charms, spells, and rituals so used." (per The American Heritage Dictionary)

Again, I believe that there is zero good evidence for anything supernatural whatsoever, so I do not believe that "real magic" exists.

However, I think that "magical" cures for physical or psychological complaints often work, even without supernatural or objective medical components. Or in other words, "doing magic" often objectively gets results, even if you didn't have the foggiest notion what's causing the problem, don't have any medicinal herbs available, etc.

Please do not misunderstand me here as saying that "real magic" is real or that there is any real supernatural aspect of magic -- I'm saying that "suggestion" and the placebo effect are effective.

I'm also a little surprised at the revival of ritual magic (or "magick"), as practiced by contemporary Neo-Pagans and "magical orders". A number of my friends have been more or less into this, and I have once or twice been a guest at fairly-informal rituals. I have to say (sorry, guys), that I also categorize such contemporary magical rituals as things that "don't work", and as pretty much a waste of time except for any psychological and social benefits. IMHO this revival is evidence that such beliefs and practices are natural to human beings.

- A page on this site on / Magic and Miracle /

A somewhat complicated subject. First of all, I feel that the evidence that UFOs are vehicles bringing visitors from other worlds is pretty shaky.

Most UFO sightings are "odd lights in the sky", and could be pretty much anything: aircraft, birds reflecting light, ordinary astronomical bodies (usually Venus), odd electrical phenomena, meteors, etc, etc.

As I said above, I think that the evidence is that brief "hallucinatory" experiences in sane ordinary people are not rare, and account for many reports of extraterrestrial beings.

I don't think that extraterrestrial beings visiting Earth would behave as the UFO aliens are reported to behave. Why be secretive? Why not just announce plainly, "We're here, we're extraterrestrials, deal with it"? When the European explorers arrived in the Americas, Asia, Africa, the fact was quickly well-known to everybody in the area.

Of course, since by definition we are talking about non-human beings, perhaps I just don't understand their psychology.

"A student asks: why should we believe in global warming?, and you respond with a meticulously logical argument, along with a citation of scientific research. ...

At length it finally dawns on you: to these kids, logic, science, rationality, are just "cultural artifacts" -- no more or less credible than witchcraft, astrology, divination, tarot cards, or plain off the wall hunches. (Who's to Say?) ...

Sadly, the virus of irrationalism has spread even to the colleges and universities of the realm, in the guise of "post-modernism” whose most extreme adherents regard competing theories of reality, such as astronomy and astrology as "social constructs" and "stories," each with an "equal right to be heard and appreciated."

Post-modernism was (or should have been) discredited by Alan Sokol's notorious hoax: A parody article, "Transgressing the Boundaries..." which the post-modernist publication, Social Text swallowed hook, line and sinker, in its Spring 1996 issue. Sokol thus describes his article as 'a mélange of truths, half-truths, quarter-truths, falsehood, non-sequitors, and syntactically correct sentences that have no meaning whatsoever.'

... there are a few fundamental features of scientific activity that most observers of science will accept, and which the ordinary non-scientific citizen might readily understand. They are also features that set science distinctively apart from non-scientific truth claims. I will discuss just seven of these features."

"Woo is a word skeptics use as shorthand to describe pseudo-scientific and often anti-scientific ideas-- ideas that are irrational and not based on evidence commensurate with the extraordinary nature of the claim. These are ideas that usually rely on magical thinking, are rarely tested to see if they are real, and are usually resistant to reason and contrary evidence."

"'Extraordinary Claims Require Extraordinary Evidence' ...

The origins of the saying can perhaps be found in Hume’s Maxim:

'No testimony is sufficient to establish a miracle, unless the testimony be of such a kind that its falsehood would be more miraculous than the fact which it endeavors to establish…'

Replace "miracle" with "extraordinary claim", and you have the basis of the quote that Carl Sagan popularized. And intuitively, most people would agree with it in principle. For example, if I told you I had cereal for breakfast, you would probably believe me. You know cereal exists and that people eat it for breakfast. Of course, I could be lying, but even if I were, I have not asked you to accept some new and extraordinary idea. (The fact that I lied wouldn’t mean that cereal somehow doesn’t exist any more.) However, if I told you that the cereal I eat every day will guarantee that I will never get sick and will live to be 100, you would probably want some evidence of that, and some pretty good evidence too.

Strictly speaking, all claims require exactly the same amount of evidence, it’s just that most "ordinary" claims are already backed by extraordinary evidence that you don’t think about. When we say 'extraordinary claims', what we actually mean are claims that do not already have evidence supporting them, or sometimes claims that have extraordinary evidence against them. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence because they usually contradict claims that are backed by extraordinary evidence. The evidence for the extraordinary claim must support the new claim as well as explain why the old claims that are now being abandoned, previously appeared to be correct. The extraordinary evidence must account for the abandoned claim, while also explaining the new one.

Most people are probably unaware of the amount of extraordinary evidence required for most scientific claims. Not only must the experiments be written up in such a way that others can challenge the assumptions and be able to spot errors, but they must also be independently replicated. In addition, most scientific discoveries have provenance -- that is, we know how and why we decided to test this claim in the first place. For example, a new drug may have a theoretical rationally as well as positive in vitro and animal testing before it is even tested on humans. Consequently, we already have reasons to suppose it might work. Compare that with much of alternative medicine, where we have no basis to suppose it works, and whose tenets we are pretty sure were just made up (A word of mild defense of alternative theories here: By "made up" we could mean "Consciously created as fiction" or "Guessed or hypothesized in an honest but baseless attempt at explanation." For example, I leave a dish of water sitting all day in the hot sun. At the end of the day, the water is gone. Ignorant people wonder how it disappeared. I could [knowing contemporary chemistry and physics] consciously deceive them by telling them "The water fairy drank it", or [being myself ignorant of contemporary science], hazard the guess "Huh. Maybe the water fairy drank it", and believe or at least half-believe this myself. However, we need to remember that, although in the second case I am not consciously being dishonest, I [and others who believe me] am still wrong.). In this case by "extraordinary evidence", all we really mean is the same level of evidence that supports real medicine.

"Not all information is created equal. Some of it is correct. Some of it is incorrect. Some of it is carefully balanced. Some of it is heavily biased. Some of it is just plain crazy.

It is vital in the midst of this deluge that each of us be able to sort through all of this, keeping the useful information and discarding the rest. This requires the skill of critical thinking. Unfortunately, this is a skill that is often neglected in schools.

This site is designed to make a point about the danger of not thinking critically. Namely that you can easily be injured or killed by neglecting this important skill. We have collected the stories of over 670,000 people who have been injured or killed as a result of someone not thinking critically."

"A short refresher course: Dharma (Department of Heuristics And Research on Material Applications) was founded in the 1970s by a couple of scientists named the DeGroots, who were greatly influenced by the work of psychologist and inventor B.F. Skinner. They were given funding by one Alvar Hanso, which allowed them to send a large team to the island to conduct research in meteorology, psychology, parapsychology, zoology, electromagnetism and Utopian social engineering.

A major reason why we know all of this is thanks to the orientation films hosted by Dr. Pierre Chang, a.k.a. Marvin Candle, a.k.a. Mark Wickmund, a.k.a. Edgar Halliwax. So what did Francois Chau, the actor who played Chang, think of all of this? ..."

Much of their research does exist in the real world, leading one to another question: Are there organizations from history that may have inspired the idea of the Dharma Initiative?

Ask many who have pondered that question, and one answer you often hear (aside from Skinner, obviously) is DARPA. DARPA - the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency - is often credited with creating the internet and has researched and developed some pretty advanced stuff, especially in the area of robotics. DARPA even sounds like "Dharma," but as tempting as it is to draw conclusions about the two, the similarities start and end there (for one thing, Dharma is a private organization).

One person who has thought about this quite a bit is blogger Klint "Klintron" Finley, who has written about the concept of "real-life Dharma initiatives" extensively at Hatch23.com. 'I think it stems from various trends and movements from the '60s and '70s,' he said. 'More specifically, anywhere that two or more of the following intersected: Eastern spirituality, fringe science, defense spending, disturbing psychological research, experiments in utopian/communal living and experiments social control.'

He points to many possible influences for the Dharma concept but thinks there is one in particular that shares a lot with Dharma: the Esalen Institute. Made famous in a 1967 New York Times article, the institute began as a place where one could, as its website says, have 'the intellectual freedom to consider systems of thought and feeling that lie beyond the current constraints of mainstream academia.'

It still serves as a retreat center at the beautiful Big Sur mountains to this day and, according to the website, has been devoted to the exploration of human potential since the 1960s. It's here that the "Physics Consciousness Research Group" was allegedly co-founded in 1975 by theoretical physicist Jack Sarfatti. Sarfatti is the author of such works as "Progress in Post-Quantum Physics and Unified Field Theory" and "Super Cosmos: Through Studies Through the Stars."

"Two children are missing in Belize, and no one knows what happened to them. So a helpful 'psychic' declared that they had been fed to the crocodiles in a nearby sanctuary. The results were predictable.Reports are that the mob shot and killed some of the 17 crocs held in captivity at the sanctuary.The sanctuary looks like it was an amazing setup: all power was provided by solar and wind, they offered educational programs, they were training students, and they were also supporting local eco-tourism. And of course their primary mission was protecting endangered reptiles.

Now it's all destroyed by the lies of one ignorant fraud, whipping up a mob into a ridiculous frenzy. Even now the people who ran the sanctuary can't come back — they've been threatened with death.

Ignorance isn't just a passive failure. Ignorance topples and destroys the great things people build up."

"In their recent article in The Huffington Post, biologist Robert Lanza and mystic Deepak Chopra put forward their idea that the universe is itself a product of our consciousness, and not the other way around as scientists have been telling us. In essence, these authors are re-inventing idealism, an ancient philosophical concept that fell out of favour with the advent of the scientific revolution. According to the idealists, the mind creates all of reality."